×![]()

Why habits are hard to break and 3 ways to make it easier

It’s not easy to change habits. For many of us, New Year’s resolutions are an opportune way to do so. We make resolutions[1] at the start of the year - to be healthier, kinder, spend more time with family, or other such goals. Unfortunately however, those promises are hard to keep. Generally, by February, 80% of resolutions[2] already broken.

A new year brings with it a pleasant air of anticipation. It’s a blank page, a fresh start - with all the related optimism and positivity. At the same time, this is when we recall the broken resolutions from previous years - and that’s a demotivator for setting new ones. Is there a solution? I believe so: we just need a better understanding of how habits work (know the enemy[3]) and the ability to seek help where needed.

Some time ago, I investigated habits and why they are so persistent. Part 4 of my book covers t this in detail (if we don’t change the habits of people in the organization, we’ll never change the culture). This New Year, I dove into that topic again, as there are still some resolutions that I find very hard to keep.

For a deeper explanation of habits and the habit loop, see my book ‘Agile Leadership Toolkit’ – Part 4.

What are habits?

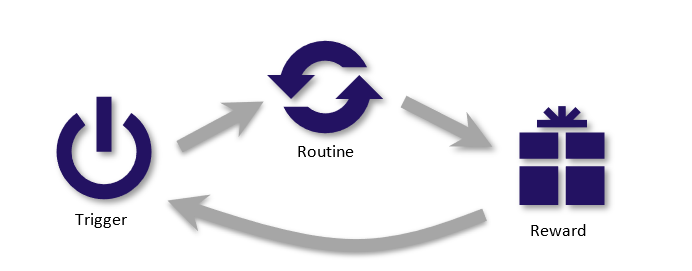

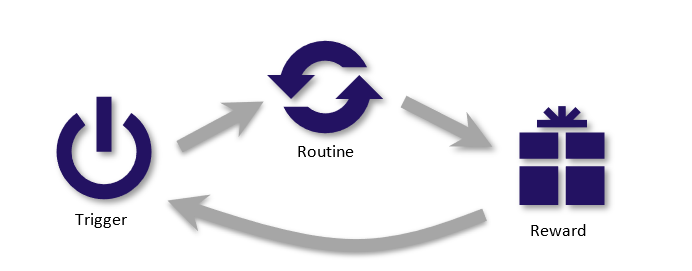

A habit[4] is a settled tendency. It’s a regular way of behaving, which we become accustomed to and don’t think about explicitly. We continuously, subconsciously execute habit after habit. Making a sandwich, driving to work, even making coffee - such actions consist of many habits. We can do these things without consuming much (or any) of our attention or energy. Habits form in a part of our brain called the Striatum (or Corpus Striatum). This cluster of neurons is the engine behind the ‘reward system’. Focused on reducing the cost of body movements and increasing their benefit, it lets us learn from when we handle things better. These efficiency learnings are then stored in our brain, ready for fast retrieval. The first time we do actions like brushing our teeth, or driving a car, we must focus on our movements. During this process, our Striatum makes numerous neuron connections, so the same movements are easier the next time. To simplify: a habit consists of three steps: trigger, routine and reward. A habit is triggered, after which the routine is rewarded. Together these three elements form the habit loop.

| Trigger The trigger is a situation, moment or event. It initiates a reaction in a person or team, as if a button has been pressed to switch the habit on. Previous (positive) experiences shape a particular behavior, which is initiated without much thought or consideration of earlier actions.. | |

| |

Routine The routine is a behavior or action that may have initially been uncomfortable, but is becoming more established. Examples include actions (like opening a door, giving feedback, or working harder) or even emotions like stress or happiness. At first the behavior might feel new or uncomfortable, but positive rewards quickly make it routine. |

| Reward The reward is a positive outcome or benefit from the behavior. It includes things like tasks becoming easier, pain prevention, and less tangible things like feeling appreciated or part of a group. The reward must be almost instant Behaviors where the reward follows hours or days later will never become routine. The reward ensures our brains make an increasingly strong connection between the trigger and the action. Over time, we begin to act without thinking about it. |

Why are habits so persistent?

Habits persist because our brain is wired for them[5] and changing behavior or body movements takes more energy (and willpower) than using an existing habit. For example, brushing your teeth with your other hand requires discipline, attention and willpower. Often, doing this different can be done for a few days, after which the old routine kicks-back. Why is this so hard to change? That’s very important to understand. The reason is that we don’t actually create a new habit, we just succumb or fallback to an existing one. Why didn’t we create a new habit? The lack of reward means no new habit forms. Brushing your teeth with your other hand is uncomfortable, time-consuming and probably less effective, so our brain’s Striatuma doesn’t make a neuron connection. In fact, it’s probably built a negative association, making it even harder to continue. Let’s go back to those New Year’s resolutions like losing weight, exercising more, or starting a new hobby. These are all positive, sought-after resolutions. However, the biggest reason why we don’t uphold our promises isn’t willpower, discipline or the fact that they are better for us, it’s the (bad) habits that prevent us from following these resolutions! Can there be any hope then for our New Year’s resolutions? Fortunately, yes, as we can use the power of a habit to change a habit. That might sound easy and unrealistic, so let's take a closer look and be practical.How can we keep our New Year’s resolutions?

The secret to keeping to our resolutions is finding the (bad) habit that’s halting us and substitute it with a better one. It’s not about suppressing the habit, but using its power to create a healthy one. Let’s have a look at the resolution to exercise more (38% of New Year’s resolutions[6]). At a given moment on a given day we will choose between doing exercise or not (sounds simple, but bear with me). It’s likely that not exercising offers a bigger reward - more time to engage with social-media, sleep, watch Netflix, or other such rewards. Exercising comes with negative results like aching muscles, or the need to tackle the rain or cold. So how can we keep this resolution? Suppressing the desire or habit to watch TV and considering the negative reward takes willpower and discipline. That works for a few weeks, but ends in February (with the other 80% of resolutions), because despite all the energy and discipline used, we didn’t create an improved habit. The key is to increase the reward from exercising - creating a positive reward, directly after doing it. That could be high-fiving your partner when you return from a run and – preferably – using the reward related to the existing habit. So after the exercise watch longer Netflix or social media. Don’t punish yourself by withholding the reward of the old (bad) habit, but use the reward to your own benefits. Even minus any feelings of failure, shame or guilt. We’ve looked at habits, why they are so hard to change, and using their power to create better habits that achieve our resolutions. Let’s close with three practical tips to drive home the benefits of our New Year’s promises.Tip 1: Don’t paraphrase the benefit, but the actual behavior

One common pitfall is to create a resolution that's clear and measurable, but based on the outcome or benefit. Losing 10kg by September 1st sounds like a good resolution, but it’s not focused on the habit or behavior needed to achieve the result. What must be done to lose weight? Probably eating less (bad) food and exercising more, so a better resolution is: ‘weekdays, after 20:00 hours, the only snacks will be fruit’. This focuses on the actual short-term behavior needed. It also creates a positive reward (if you like fruit) and doesn’t suppress the old reward (the taste of unhealthy snacks). At the same time, it’s tangible and measurable.Tip 2: Don’t paraphrase avoidance, but action

A recent study of 1600 participants on New Year’s resolutions[7] concluded that avoidance phrases (e.g. stop eating chocolate) are less productive than achievement phrases (e.g. go for a walk after lunch). The avoidance phrase focuses on the (strong) old habit and requires more discipline and resilience to beat.Tip 3: Avoid stand-alone habits, attach them to existing ones

BJ Fogg from Stanford University has a powerful theory on habits, and it’s also based on using their own power to change them. His book ‘Tiny Habits’[8] advocates attaching a new habit to an existing one. Take for example a goal to strengthen your upper-body, with a resolution to visit the gym every Friday. The trick is to also create a tiny habit, for example; after brushing my teeth, I do some push-ups, after which I’ll shout ‘yeah!!’. Two actions are key here. Firstly: attach. Your (hopefully) current habit of brushing teeth becomes a trigger for the new habit. Secondly: reward. This should be something positive. It can be small (like shouting ‘awesome’), but it is mandatory and can’t be negative. Although many New Year’s resolutions fail, some easy tricks can help us maintain and really benefit from our ambition to improve ourselves. Knowing the power of habits and, rather than fighting them, using their power to harvest improvements, is crucial. I hope these three practical tips will help you to keep at least one resolution. Last but not least: be prepared to ask for help if you need it. Regular support from a friend, and their capacity to check in on how you are doing are great motivators. Feel free to comment on this article or contact me via LinkedIn to talk about your resolutions and how you can achieve them.References

- [1] 44% of the americans - http://maristpoll.marist.edu/npr-pbs-newshour-marist-poll-national-survey-results-analysis-2019-new-years-resolutions

- [2] 80% fail by February - https://health.usnews.com/health-news/blogs/eat-run/articles/2015-12-29/why-80-percent-of-new-years-resolutions-fail

- [3] General Sun Tzu - https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/17976

- [4] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/habit

- [5] https://bcs.mit.edu/news-events/news/wired-habit

- [6] http://comresglobal.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/BUPA_NY-Resolution_Public-Polling_Nov-15_UPDATED-TABLES.pdf

- [7] https://www.inverse.com/mind-body/largest-study-on-new-years-resolutions-explained

- [8] https://www.tinyhabits.com/